Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Body Composition and the Derivatives of Reactive Oxygen Metabolites & Biological Antioxidant Potential

Article information

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

This study was to investigate the effects of aerobic exercise at different intensities on body composition and the derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites & biological antioxidant potential.

METHODS

The recruited subjects of thirty young men without any medical problems were divided into LEAI(light-exercise aerobic intensity, n=10), MEAI(moderate-exercise aerobic intensity, n=10), and VEAI(vigorous-exercise aerobic intensity, n=10). The variables were measured to the body compositions (%body fat, BMI & WHR) and the derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites & biological antioxidant potential) on pre-and post-exercise protocol programs for 8 weeks. The collected blood samples from a fingertip were analyzed with FRAS evolve, H & D co., Italy. Statistical analysis used the two-way repeatedmeasures ANOVA and Tukey’s test for post-hoc analysis and test of homogeneity with Levene’s F value.

RESULTS

The results are as follows; In body compositions, %body fat was shown a significant difference between pre-and post-exercise in the VIAE group and a significant difference between LIAE & VIEA and MIEA group in post-exercise. WHR(waist to hip ratio) was shown a significant difference between LIAE & VIEA and MIEA group in post-exercise. The oxidative stress, d-ROM(derivatives of Reactive Oxygen Metabolites) was not shown a difference significantly, and BAP(Biological Antioxidant Potential) significant difference between pre-and post-exercise in LIEA & VIEA groups.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, it increased oxidative stress parameters, the derivatives of Reactive Oxygen Metabolites, and Biological Antioxidant Potential in each group after 8 weeks of exercise. The antioxidant defense system was revealed to ensure biological safety in regular exercise situations.

서론

산화적 스트레스(oxidative stress; OS)는 항산화력(antioxidants defenses)과 활성산소(free radical) 생성량 사이의 불균형으로[1] 인체는 생명을 유지하기 위하여 산소를 필요로 한다. 이러한 과정에서 일부의 산소들이 반응성 산소종(reactive oxygen species; ROS)으로 변화하는데 이것이 활성산소(free radical)이며, 항산화 효소(antioxidant enzymes)가 이들의 균형을 유지하는 데 작용을 한다[2]. 즉 활성산소 생성을 억제하고 중화하는 항산화 효소와 같은 항산화력은 인체 내에서 산화적 스트레스의 균형을 유지하기 위하여 세포 내 방어벽을 생성하여 활성산소에 의한 피해를 최소화한다[3]. 그러나 스트레스, 흡연 그리고 비만 등의 여러 가지 요인이 ROS의 생성을 촉진하며[4], 산화적 스트레스는 심혈관계 질환, 암, 신경계와 호흡계, 그리고 근골격계 질병을 유발하는 원인이다[5]. 이러한 질병은 비만(obesity)과 관련이 있으며, 산화적 스트레스를 유발하는 비만의 질환에 대한 병인을 이해하는 것이 중요하다. 즉 건강인의 경우 ROS가 시상하부의 식이조절기전을 가능하게 하나 비만인은 다량의 ROS를 발생하여 식이조절을 어렵게 한다[6]. 또한 비만은 혈중 유리지방산을 높여 지질과산화 이온의 급격한 생성을 자극하며[7] 이때 독성 물질이 체내에 축적되어 세포의 손상 및 대사의 변이를 일으킨다[6]. 이와 같이 비만은 산화적 스트레스와 깊은 연관성이 입증되고 있으며 산화적 스트레스의 균형을 유지하여 각종 질병으로부터 벗어나 건강을 유지하기 위해서는 비만의 예방 및 완화가 중요하며 운동과 과일 및 채소 섭취 등의 식이요법을 강조하였다[8]. 한편, 질병을 예방하고 체력을 증진하기 위하여 많은 사람들은 운동을 즐기고 있으나 강도 높은 운동은 ROS 생성을 유발하여 세포의 구조에 악영향을 준다[9]. 운동이 지질과산화 농도의 저하 및 체지방, 혈중지질, 그리고 혈당 등의 신체구성 성분을 개선하지만[10], 강도 높은 운동시 많은 산소가 필요하며 불가피하게 ROS가 증가하지만 세포 내에서 아군(friend) 혹은적(foe)의 역할을 한다[11]. 중강도 운동은 최적의 ROS 생성하고 항산화력의 수준을 높이는 반면에 고강도 운동(high intensity exercise)은 ROS 생성을 유발하고 세포는 이에 최대한 적응한다[12]. 그러나 운동 강도가 높을수록 활성산소와 항산화력을 증가하여 격렬한 운동은 오히려 건강에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다[13]. 운동과 관련하여 산화적 손상은 분명하지만(unequivocal) 운동 강도와 기간에 따라 다양하다[14]. 그러나 운동방법에 따른 ROS 억제와 관련하여 저항성 운동[15]과 유산소성, 무산소성 그리고 혼합 운동시 ROS와 항산화력에 관한 연구가 보고되었다[16-17]. 이와 같이 운동과 관련하여 ROS와 항산화력의 산화적 스트레스에 대한 많은 연구가 수행되고 있으나 국내의 연구는 미진한 실정으로 운동방법, 대상 및 실험설계를 고려한 지속적인 연구가 필요하다.

따라서 본 연구의 목적은 운동강도에 따라 유산소성 8주 운동 전·후 신체구성 요인과 혈중 반응성 산소종 및 항산화력의 차이를 규명하여 운동강도에 따른 유산소성 운동시 효과적인 운동처방 자료를 제공하고자 하였다.

연구방법

1. 연구대상자

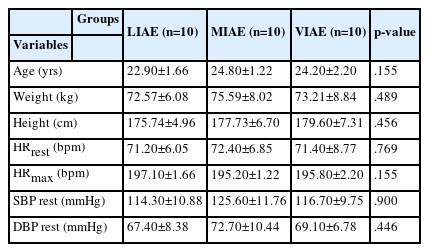

본 연구의 대상자는 G도 소재 대학교에 재학 중인의학적으로 질환이 없고 운동에 자발적으로 참여한 남학생 30명을 저강도(light-intensity aerobic exercise, LIAE; n=10), 중강도(moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, MIAE; n=10), 그리고 고강도(vigorousintensity aerobic exercise, VIEA; n=10) 운동 집단으로 무작위 분류하였다[16]. 대상자들에게는 실험 참가 전 실험의 안전성과 연구 방법, 목적 그리고 절차 등에 관하여 설명하였으며, 서면으로 동의서를 받은 후 실험에 참여하도록 하였다. 연구대상자의 신체적 특성은 <Table 1>과 같다.

2. 실험절차 및 측정방법

본 연구에 참여한 연구대상자는 최소 8시간 이상의 공복 상태를 유지 한 후 운동 프로그램 시작 전 사전검사와 8주 운동 프로그램이 끝난 후 각각 변인을 측정하였다. 측정 변인으로는 신체구성 요인(Weight, Height, %body fat, BMI, WHR)과 기초의학변인(HR, SBP, DBP) 그리고 산화적 스트레스 지표 혈중 반응성 산소종(derivatives of Reactive Oxygen Metabolites, d-ROMs)과 항산화력(Biological Antioxidant Potential, BAP)이다. 신체구성 변인은 생체전기 저항 측정기(Inbody 720, Biospace co. Korea)를 사용하여 측정하였다. d-ROMs과 BAP을 분석하기 위하여 손가락 끝 모세혈관에서 채혈하고 채혈된 혈액은 곧바로 튜브에 옮겨 국제과학협회에서 인증 받은 산화적 스트레스 분석 시스템(FRAS evolvo, H & D co. Italy)을 이용하여 분석하였다. 이 방법은 스핀공명법(electron spin resonance; ESR)과 비교하여 타당도가 매우 높은 것으로 알려져 있다.

3. 운동 프로토콜

본 연구를 위한 운동 프로그램은 총 8주 실시하였으며 3일/주, 회당 50분씩 구성하였다. 1회 50분 운동은 준비, 운동 5~10분, 본 운동 30~40분, 정리운동 5~10분으로 구성하였다. 운동은 트레드밀을 이용하여 실내에서 진행하였고 운동 강도는 여유 심박수(heart rate reserve, %HRR) 방법을 이용하여 THR(target heart rate) = [(HRmax - HRrest) × % intensity desired] + HRrest와 HRmax = 220–age[18]로 산출하였다. 운동 강도에 의한 집단구분은 ACSM 기준[19]에 의하여 저강도(30~39%HRR), 중강도(40~59%HRR), 그리고 고강도 운동집단(60~85%HRR)으로 분류하였으며, 구체적인 목표 운동 심박수 범위(range of lower - upper limit)와 운동 중 평균 심박수는 <Table 2>와 같다. 이때 운동 강도는 무선 심박수 측정기(Bodypro M100, Du-Sung tech. co., Korea) 를 이용하여 %THR를 실시간으로 모니터링하고 운동 강도를 조절하였다.

4. 자료처리

본 연구의 결과 분석을 위한 자료처리는 SPSS 26.0(ver. Korea) 통계 프로그램을 이용하였고 모든 측정항목은 평균(m)과 표준편차(SD)를 산출하였다. Levene’s F 검증을 통해 정규성 분포와 동질성을 검증한 후 이원반복측정 분산분석(two-way repeated measures ANOVA)을 하였다. 집단 간 운동 전・후 차이는 paired t-test, 운동 강도 집단 간 차이는 일원배치 분산분석(One-way ANOVA)하고 Tukey’s method으로 사후검증 하였다. 통계학적 유의수준은 α=.05로 설정하였다.

결과

1. 신체구성(Body composition)의 차이

운동 강도에 따른 트레드밀 운동 전・후 신체구성은 <Table 3>에 제시한 바와 같다. 신체구성 요인 BF(%body fat)은 측정시점과 운동 강도 상호작용에서는 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았으나, 고강도(VIAE)에서 운동 전・후 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타났다(F=9.592, p<.01). 운동 전・후 강도 간에는 유의한 차이가 나타났으며(F=4.358, p<.05), 사후검증결과 저강도(LIAE)와 중강도(MIAE)(p<.05), 고강도(VIAE)와 중강도(p<.01) 각각 유의한 차이가 나타났다. BMI는 측정 시점과 운동강도 상호작용에서는 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았으며, 운동 전・후(시기) 및 운동 강도(집단) 간에도 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았다. Waist to hip ratio (WHR)는 측정시점과 운동 강도 상호작용에서는 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았으나, 운동 후 강도(집단)간 유의한 차이가 나타났다(F=5.375, p<.05). 사후검증결과 운동 처치 후 중강도(MIAE )는 저강도(LIAE)(p<.05) 및 고강도(VIAE)(p<.01)와 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타났다.

2. 혈중 반응성 산소종(d-ROMs)과 항산화력(BAP)의 차이

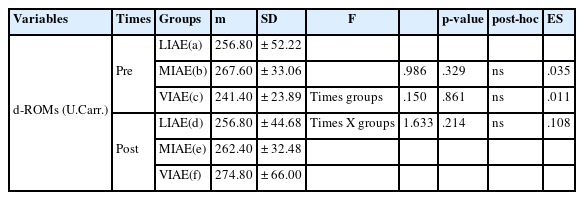

산화적 스트레스 지표 혈중 반응성 산소종(derivatives of Reactive Oxygen Metabolites, d-ROMs)과 항산화력(Biological Antioxidant Potential, BAP) 차이는 <Table 4>, <Table 5>에 각각 제시한 바와 같다.

<Table 4> d-ROMs는 측정시점과 운동강도 간 상호작용에서는 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았다. 운동 전・후 집단(F=.986, p=.329) 및 강도 간(F=.150, p=.861)에서 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았다. <Table 5> BAP은 측정시점과 집단 간 상호작용에서는 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았다(F=1.728, p=.179). 운동 전・후 집단 간에 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았다(F=.065, p=.937). 운동 전・후 강도 간에 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타났으며(F=18.791, p=.000), 사후검증(paired t-test) 결과 운동 전・후 저강도(LIAE)와 고강도(HIAE) 집단에서 유의한 차이(p<.05, p<.01)가 각각 나타났다.

논의

본 연구는 저강도, 중강도 그리고 고강도의 운동강도로 8주간 운동 전·후 신체구성과 혈중 반응성 산소종(d-ROMs) 및 항산화력(BAP)의 변화를 규명하고 논의하면 다음과 같다.

항산화 방어 시스템은 산화적 스트레스의 영향을 방어하는 중요한 역할을 한다[22]. 그러나 항산화 방어 능력이 ROS를 제압하지 못하고 산화적 스트레스가 발생하면 염증 전 물질이 발생한다[23]. 연구에 의하면 산화적 스트레스는 지방세포의 증식 및 분화뿐만 아니라 지방세포의 크기를 자극하고 비만은 백색 지방조직의 증식을 특징으로 하며[24]. 이러한 비만은 산화적 스트레스 발생의 중요한 요인이며 가능성이 있는 것으로 알려져 있다[6]. 본 연구의 체지방율(%body fat)은 고강도 운동집단에서 감소하여 중강도와 고강도 수준의 유산소 운동을 하면 체중 감량에 효과적이라는 운동지침 연구결과와 일치하였다[25]. WHR는 운동 후 모든 운동강도에서 감소하였는 데 이는 45~55%HRR 운동강도로 8주간 운동시와 유사한 결과를 얻었다[26]. 이러한 결과는 유산소 운동이 신체구성의 변화에 긍정적인 변화를 보고한 선행연구[27]와 유사한 결과로 유산소 운동은 지방이 에너지원으로 동원이 증가하도록 유도하여 에너지 소비와 지방 대사가 더욱 원활하게 진행됨에 따라 체지방이 감소한 결과로 생각된다.

운동시 ROS와 항산화력 관련하여 낮은 운동강도와 짧은 운동 기간 등의 운동 프로토콜은 효과적으로 항산화 방어기전이 작용하지만 운동강도와 기간이 증가하면 산화적 스트레스를 효과적으로 제어할 수 없으며[28], 최대 강도에서 운동시 ROS와 항산화력이 증가하나 운동 후에는 신체능력이 높은 사람들이 낮은 산화적 스트레스가 나타났으며[29], 유산소성 운동은 ROS를 완화한다고 하였다[16]. 유산소성 운동 65%~75% VO2max에서 지속 운동시 40% VO2max 이하와 비교하여 많은 양의 ROS가 발생하며 근 수축 온도가 높을수록 ROS 발생을 높이며[30], 짧은 운동시간 혹은 VO2max 30% 이하 강도에서 운동시 산화적 스트레스는 촉진되지 않으나 훈련되지 않은 사람은 1회성 장시간 지구성 운동에서도 혈중이나 활동성 근골격에 산화적 스트레스 지표가 증가하였다[31]. 또한 지구력 운동시 훈련된 근육에서 항산화제 효소활성이 증가하여 일회적 운동시 발생하는 산화적 스트레스를 완화한다[15]. 본 연구의 혈중 반응성 산소종 d-ROMs(derivatives of Reactive Oxygen Metabolites)의 변화를 살펴보면 모든 운동 집단에서 운동 전・후(시기) 및 운동강도(집단) 내에서 증가하였으며 고강도 운동집단에서 운동 후 가장 크게 증가하였다. 이러한 결과는 운동강도가 높을수록 ROS가 증가한다는 선행연구와 유사한 결과가 나타났다[13]. 본 연구의 항산화력 BAP(Biological Antioxidant Potential)의 변화를 살펴보면 운동 전・후 저강도 운동집단과 고강도 운동집단에서 통계적으로 유의하게 증가하였으며 중강도 운동집단에서는 유의하게 증가하진 않았으나 운동 후 증가함을 알 수 있었다. 이러한 결과는 운동 후 활성산소의 증가와 더불어 이의 완충을 위한 대응 방안으로 항산화력이 증가한다는 선행연구 결과[32] 및 지구성 운동시 훈련된 근육에서 항산화제 효소활성은 운동시 발생하는 ROS를 완화하기 위한 기전의 연구 결과와 유사한 결과이다[10]. 그러나 낮은 운동강도와 기간 그리고 운동 프로토콜은 효과적으로 항산화 방어기전이 작용하지만 운동강도와 기간이 증가함으로써 산화적 스트레스를 효과적으로 제어할 수 없다고 하였다[28]. 따라서 본 연구의 저강도 운동시 항산화력의 증가는 낮은 운동강도에서 산화적 스트레스를 효과적으로 제어하기 때문이며[28], 운동 강도가 높을수록 활성산소와 항산화력을 동반 활성화는 산화적 스트레스의 균형을 유지하기 위한 기전이라 생각된다[13]. 이와 같이 산화적 스트레스에 관한 다양하고 많은 연구가 시도되고 있으며 다양한 결과들이 도출되는 만큼 운동방법에 따라 산화적 스트레스에 관한 연구를 지속적으로 수행하여 건강 유지 및 증진을 위한 과학적 운동방안을 도출할 필요가 있다.

결론

본 연구는 저강도, 중강도 그리고 고강도의 운동강도로 8주간 운동 전·후 신체구성과 혈중 반응성 산소종(d-ROMs) 및 항산화력(BAP)의 변화를 규명하고 다음과 같은 결론을 얻었다.

첫째, 신체구성 요인 %BF(%body fat)은 고강도 운동 전・후 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타났다. 운동 후 저강도와 고강도 운동은 중강도 운동과 유의한 차이가 각각 나타났다. WHR(waist to hip ratio)은 운동 후 저강도와 고강도 운동은 중강도 운동과 유의한 차이가 각각 나타났다.

둘째, 혈중 반응성 산소종(d-ROMs)은 운동 시기 및 집단 내에서 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았다. 항산화력(BAP)는 운동 전・후 저강도 운동과 고강도 운동에서 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 나타났다.

이상의 결과를 종합하면 혈중 반응성 산소종 및 항산화력 등이 다양한 운동강도에서 운동 후 증가하였다. 이러한 결과는 활성산소와 항산화력의 균형을 유지하기 위한 기전으로 판단되며, 비만이나 연령 그리고 체력수준 등을 고려한 다양한 연구상황에서 건강을 위한 최적의 운동방법을 모색하고자 한다.

Notes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.